I recently had the pleasure of interviewing Ken McLeod about the Diamond Sutra for my Deconstructing Yourself podcast. Ken is an amazing teacher and translator of Tibetan Buddhism who has been retired for years, but he said that he wanted to talk to people about the power of this very ancient Buddhist scripture. Most people, he said, tend to read the Diamond Sutra as a philosophical document, but McLeod has come to see it as a “pointing out instruction”—a direct teaching on the nature of mind. Here is an excerpt of that interview, which will be coming out as a full podcast soon. Ken will also be finishing up his six-week Alembic series on the Diamond Sutra over the next few weeks; on-line tickets (which give you the previously recorded evenings as well) are still available.

— Michael Taft

Ken McLeod: The correct name for the Diamond Sutra is the “sutra of the vajra that cuts.” “Vajra” was improperly translated as “diamond,” which isn’t really accurate. It refers to the weapon that Indra, who was originally a rain god in India, wielded. It’s the idea of an instrument that is so powerful that it can cut anything without being harmed itself. So, “diamond” is not an unsuitable substitution.

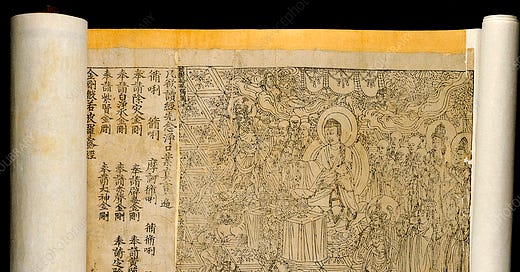

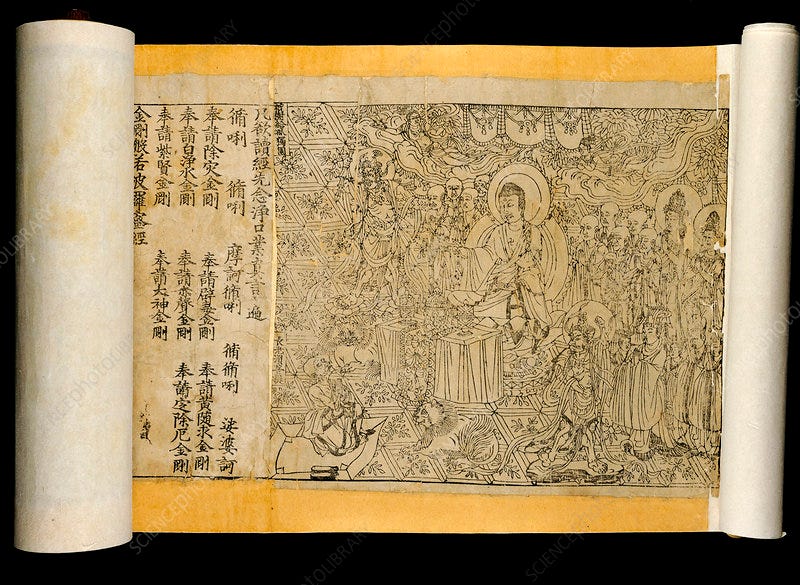

Michael Taft: The Diamond Sutra is the first printed book that we have that was dated. The date is the 11th of May 868.

KM: Which goes to show how highly regarded it was, to be the earliest one that has come down to us. It’s a very important text in the Chinese tradition. It was very influential in the formation of Chan in China, which became Zen in Japan. So it has a very important place in the Japanese Zen tradition as well.

MT: So this sutra became central to several different Buddhist traditions in Asia and is generally recognized as a major sutra. The last time I read it was decades ago. It reads like a kind of Zen paradox. It’s like a dry philosophical text that's making a point that is either really easy to get or incredibly hard to get.

KM: It’s not a text that you understand in the conventional way. It uses language to stop the mind. Now, for many people it feels like they're being thrown into confusion and they resent it. The problem with this mode of eliciting experience is that if a person isn't ready for it they feel like they've been tricked, or put down, or they aren't up to it, or something like that. So it can elicit a lot of negative feelings. That isn't actually what's going on. This is something that has to really mean something to you, because otherwise you may end up in a place that you don't want to be. That's just my little warning note.

MT: This text comes to us from around the beginning of the Mahayana era, when the Mahayana view is coming together. I think it's really interesting that whoever composed the sutra seemed to have really nailed it on this very early attempt. They also seem to have done a really good job of trying to put you in the mood of understanding something that, in a way, can't be understood with your regular way of thinking.

KM: It’s often regarded as one of the earliest of the extant Prajnaparamita or Perfection of Wisdom Sutras. In fact, that's part of its name, the Vajra Cutter Perfection of Wisdom Sutra. And that is very interesting from that point of view, because the word emptiness doesn't occur anywhere in the text. The way I read it now is that it was [written] when the Mahayana was beginning to develop as its own tradition with its own perspective. It’s moving to a much more expansive philosophy in which all experience is seen as lacking any sense of intrinsic existence. This is one of the first efforts to put this perspective into language.

MT: What are we being led to know in the Diamond Sutra?

KM: Primarily, what it means to be awake. Suppose you're dreaming and you know that you're dreaming and in this lucid dream a woman comes up to you and she's crying inconsolably. You know this is a dream. You know there's no woman there, that it's just something that's arising in your dream. What do you do?

MT: I imagine even in the context of a lucid dream you try to relieve her suffering.

KM: Why? There's no suffering there, just something that's happening in your mind. Why?

MT: I feel like it's just the natural thing to do rather than just sit there and ignore her.

KM: Okay. Do you even think about it?

MT: Well, that's what I mean. That's why I'm using the word natural. It's just what you do. You reach out and help.

KM: Even though there's nothing there?

MT: I would contest that there is something there. It’s not nothing. There’s an experience occurring, even if it’s a dream experience. There's something about the heart that responds to that plea, even in a dream.

MK: I think you can go a lot further than that. I pushed you a little bit when I said, "Do you even think about it?" And you said, "No, it's just there." To put this into Buddhist jargon, you know the woman is empty. You know the suffering is empty. You know that in a certain sense there's nothing there. It's empty and, as you say, you experience it vividly, with clarity, and the immediate response is compassion. Are you with me?

MT: I believe that's what I was saying, yes.

KM: Yeah. Well, in the Nyingma tradition, that is exactly how mind nature is described: In essence, empty. In nature, clarity. In manifestation, compassion. So, the Diamond Sutra predates the development of the Nyingma tradition by 800 years, give or take, but there it is. That, I think, is what the Diamond Sutra is pointing to. Not by trying to explain it. Not by trying to describe it. But to put you there. If you aren’t paying attention to what is happening as you read the sutra you miss what the sutra is trying to communicate. Most people are struggling to understand it, and they miss it completely.

MT: That was certainly my experience long ago. I got even then that it’s pointing beyond concepts, but I was not paying attention to what happened when I read it, I was just thinking about what it meant.

KM: Yes, that’s what we usually do. And if you really want to know what these sutras are communicating then you have to be paying just as much attention to what is actually happening as you are to taking in the words. So what I'm going to try to do in this course at the Alembic is, through individual interactions, take people through, just the way I was taking you through this. Maybe go a little further, so the people notice that something shifted in the way they experience, maybe just for a fleeting instant. But every one of those that you actually notice becomes a seed for something else to grow. That's really the point here.

MT: Why do you think it is that the text never uses the term emptiness? Was it written before that became a popular way of understanding this way of seeing?

KM: That's the conclusion I've come to. I don’t think emptiness had begun to be used because it doesn’t occur in this text, however there are indications that it was floating around. The Indians didn’t invent mathematical zero, but they were the first ones who really made big use of it. They discovered if I put one and then I put a zero after it to indicate the units, then the one is promoted to ten. Then I could put another zero behind that, and another zero behind that, and they discovered they could make arbitrarily large numbers by putting nothing after a digit. Nothing being zero, if you see what I mean.

TM: I do. Such a powerful concept.

KM: It is extraordinary. So, in the Diamond Sutra, periodically they get into these huge numbers to describe merit or goodness, however you want to translate it. So, the power of zero or the power of nothing was floating around. Somewhere along the line, somebody had the idea of saying experience is nothing, in the sense that experience is zero, experience is empty. That has become such a powerful way of pointing people to the lack of definite existence in everything we experience that it has endured for well over 2000 years. Not bad.

And it survived translation from language to language. In every language, and it's been going on in English for several years now, people say, “can’t we use another word besides emptiness or empty?” You can run through them and you never find a word that works as well.

Then you had to counteract the tendency to make nothing into something. For this you had Saraha, probably around the third or fourth century saying, “Those who believe in reality are stupid like cows. Those who believe in emptiness are even stupider.”

MT: Don't make emptiness into a thing.

KM: That was the message, yes. So, the Diamond Sutra is all before that very sophisticated vocabulary around emptiness developed.

MT: What else is it pointing us towards?

KM: There’s some very interesting things. At one point Subhuti says, “500 years from now, when the dharma has decayed, will there be any beings who will be able to understand this?” Buddha just says, “Don't even think like that, Subhuti.” Here is a very powerful message where Buddha is absolutely pointing to the timelessness of what is being talked about. To talk about these things degenerating and disappearing from the world is an unfortunate way of thinking, actually quite problematic, because in a sense you’re making yourself special. It doesn't belong to any particular culture or any particular age. It is something that is deeply, deeply, you could say, actually at the core of human experience.

MT: I have another question. I asked you a few days ago to provide which translation people should read, and you sent me like nine translations rather than just telling people, "Read this one."

KM: Did it end up being nine?

MT: It was a lot, yeah. But then you provided a suggested practice to prepare for the class, which is to read the sutra, to stand up and read it aloud.

KM: The whole thing, once a day.

MT: The whole thing, yeah, once a day. And, you know, I'm reminded of the original desert fathers reading the Psalms once a day, so it brought up a lot of interesting stuff for me. But I'm just curious, why would you give people this assignment? Why do we stand up and read the Diamond Sutra aloud once a day?

KM: When you stand up and read aloud, things happen that do not happen when you are sitting down and reading silently. Your whole body is involved and thus by doing this you are planting the sutra in your body. You're planting it in your speech and you're far more likely to become aware of what is happening in you as you read the sutra.

MT: Interesting. So it takes us out of the normal mode of just sitting and intaking information.

KM: This is not about information. It's not about information at all. This is pointing-out instruction.

Practicing the Diamond Sutra with Ken McLeod happens Tuesdays at The Alembic through August 6. The in-person class is sold out, but tickets are available to access this special event via livestream and recorded video on a donation basis. If you’d like to hear more of Michael’s conversation with Ken McLeod, follow the Deconstructing Yourself podcast, where the full audio will be posted in an upcoming episode.

If you enjoyed this issue of Transmutations, we think you’ll appreciate these upcoming events:

Deconstructing Yourself with Michael Taft

Thursdays, 6:30 PM: A weekly drop-in guided meditation (approximately one hour) plus Q & A with Berkeley Alembic founding teacher Michael Taft. We extend beyond any particular religion or technique in order to welcome any and all who are interested.

Transmutations is a biweekly publication from the Berkeley Alembic, a transformational center that offers classes, workshops, retreats, and warm cups of tea.